The case of Sudano-Sahelian area.

In the Adamaoua and Nord regions, savannah is the dominant plant formation. The Far North region, on the other hand, is located in the Sahelian zone. In this area, works with raw or baked clay is highly developed. In addition to seasonal agricultural activities, the region’s architectural production is significant and presents several facies.

Talking about the material culture of northern Cameroon, there is a need to include the raw earth civilization, which responds to the need to adapt to a region that offers specific building materials. Two particularities stand out when observing the buildings in this part of the country.

In the Mandara Mountains, the landscape features numerous massifs and inselbergs that reside to several ethnic groups, the majority of which are Kirdi. Architectural evidence shows that the populations opt for two solutions when building their homes. They choose between constructing the base of the wall with stones and either the rest in cob or construct the entire vertical section in rubble stone. Traditional dwellings, as seen in the field, reflect this approach. In the mountains, irregular construction predominates. These display the use of more or less squared stones. Stone stabilizes load-bearing structures and corrects ground topography. Overall, the construction of architectural works favors round shapes.

Most hut roofs are conical and covered with seko. This plant species does not tolerate the heat that prevail in the region during the dry season. It thrives on hillsides and plains. It is commonly use in the northern part of Cameroon. Technicians obtain their supplies from seko mat sellers. The latter are farmers who give up farming in the dry season to collect and sell straw. According to our observations, builders frequently use millet stalks to make roofs. In Adamaoua and the North, the savannah provides the thatch to cover ceiling.

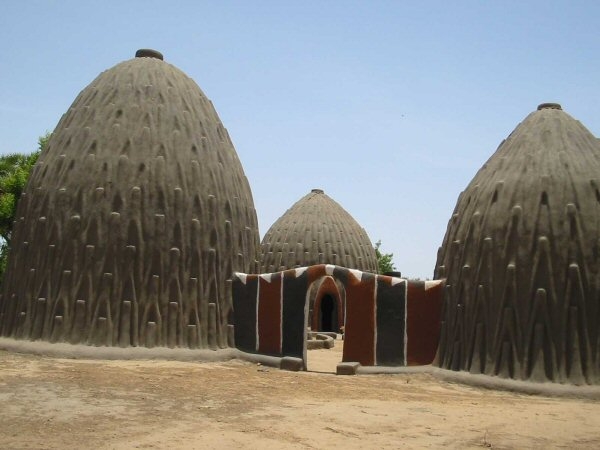

The historical importance of the northern plains is not only linked to their agricultural, fish-farming, and pastoral activities. They are better known for their architectural production. Alongside the usual round traditional huts, there are two singular types of architecture, the most significant symbols of which are the shell hut and the Kotoko mud house. In these spaces, two morphologies coexist. The Mousgoum are predominantly ovoid (left), while the Kotoko are quadrangular (right). Except for these entirely earthen constructions, the plains dwellers use cob to line the walls of their huts and granaries.

Cob and adobe are ancient building techniques used in regions where wood is in short supply. In Cameroon, cobs are of common knowledge in the Sudano-Sahelian zones. Without chronological data, it is impossible to pinpoint the origins of the technique. According to observations made in the field, the builders take the earth from the vicinity of the construction site. More often than not, they salvage the walls of dilapidated huts and crush them. The ground obtained is mix with plants or goat dung. The whole is degreas with sand. The heterogeneous mixture is sprinkled with water and left to rest for hours.

The plant species most frequently used in the preparation of cob are seko and rice stalks. The enriched ground, with straw debris, is kneaded by one or two feet until the desired consistency achieved. This homogeneous mixture is called cob. Preparing the material takes around thirty minutes and requires considerable physical effort. However, the composition of cob varies according to people, places, recipes, and resources.

Among the Kotoko of Makari, additions such as small bones, shells, and pottery shards are use to make cobs. It amounts to adding aggregate to obtain a texture similar to concrete, to enhance the drainage-drying properties of the material and increase its strength and hardness. Traveling through Mousgoum country, the main area for shell huts, we discover that they are round dwellings measuring 3 to 5 meters with just one opening: the entrance and exit door. The shell hut disappears.

When building homes, every builder plans its construction work, preferably during the dry season. In the morning, he prepares the quantity of cob he will use through the day. Once the site is mark out with a hoe, the technician cuts the cob into clumps by hand. The material is spread out along the contour of the plan, forming a 15 cm-high base layer. The cob is lay in successive layers from bottom to top. The process is performed until the desired wall height is obtain, usually no more than 3 meters. Once the wall is built for an average of seven days, work begins on the conical roof. The roof framework is made of poles tied together and strengthened with rings. The roof is thatch to form a bouquet at the top. The interior is often well laid out and covered with sand.

Intellectual property potential

Through our study of architecture in the Sudano-Sahelian region of Cameroon, we realize the enormous intellectual property potential. From the materials selected and their composition to the design of the huts built, and finally to the originality in terms of utility that arouses our curiosity.

As for the type of materials used to build hut walls in the Sudano-Sahelian zone, these are chosen according to what their environment offers; in this case, due to the lack of wood, these inhabitants use cob. The mixture’s composition dates back to when knowledge of concrete manufacturing was unknown. But thanks to quite specific formulations, they achieved an almost similar blend. This traditional knowledge has lasted for generations.

In addition to these materials, we should note that the designs of the huts (shell huts, for example) hint at astonishing originality; indeed, the shell cabane is a windowless dome with a single door serving as entrance and exit (yet a classic dwelling house requires doors and windows), having the particularity of not letting heat through (the Sudano-Sahelian area being in a very high-temperature zone). A double intellectual property value is thus perceived: originality in design and non-obviousness in technical innovation. One question remains. Can’t we use the tools offered by intellectual property to protect, enhance, and even exploit this traditional architectural know-how?